A Practical Guide to Offshore Oil and Gas Work: Roles, Safety, and Career Paths

Introduction

Offshore oil and gas work powers a significant portion of the world’s energy supply and supports thousands of skilled jobs. For newcomers, the sector can seem both alluring and intimidating: steel islands at sea, complex machinery humming around the clock, and teams whose decisions carry real-world consequences. This guide clarifies what happens offshore, who does the work, how safety is managed, what life is like between helicopter trips, and how to build a sustainable career. Whether you’re exploring entry-level roles or eyeing technical leadership, you’ll find practical context, realistic expectations, and actionable steps.

Outline

– Section 1: What Happens Offshore — Roles, Teams, and Daily Operations

– Section 2: Safety Culture and Risk Management — Systems That Protect People and Assets

– Section 3: Life at Sea — Rotations, Wellbeing, and Logistics

– Section 4: Technology, Environment, and Project Types — How the Work Is Evolving

– Section 5: Getting Hired and Moving Up — Training, Certifications, and Career Planning

What Happens Offshore — Roles, Teams, and Daily Operations

Offshore installations function like compact industrial towns. Operations continue 24/7, anchored by teams that rotate in 12-hour shifts to keep wells producing and assets secure. At a high level, the work falls into several streams: drilling and well services, production operations, maintenance and inspection, marine and logistics, and health, safety, and environment oversight. These functions interlock; a planned compressor shutdown for maintenance, for example, is timed with production adjustments and marine schedules to minimize disruptions.

Drilling and well services personnel handle the creation and upkeep of wellbores. Roles include floor crews, derrick specialists, drillers, and well intervention technicians. Production teams monitor pressures, temperatures, flow rates, and separation processes that turn a multiphase mixture into saleable oil and gas streams. Maintenance groups—mechanical, electrical, instrumentation, and control—perform routine tasks (lubrication, filter swaps, calibrations) and corrective work (pump changes, valve repairs) to prevent small issues from cascading into outages.

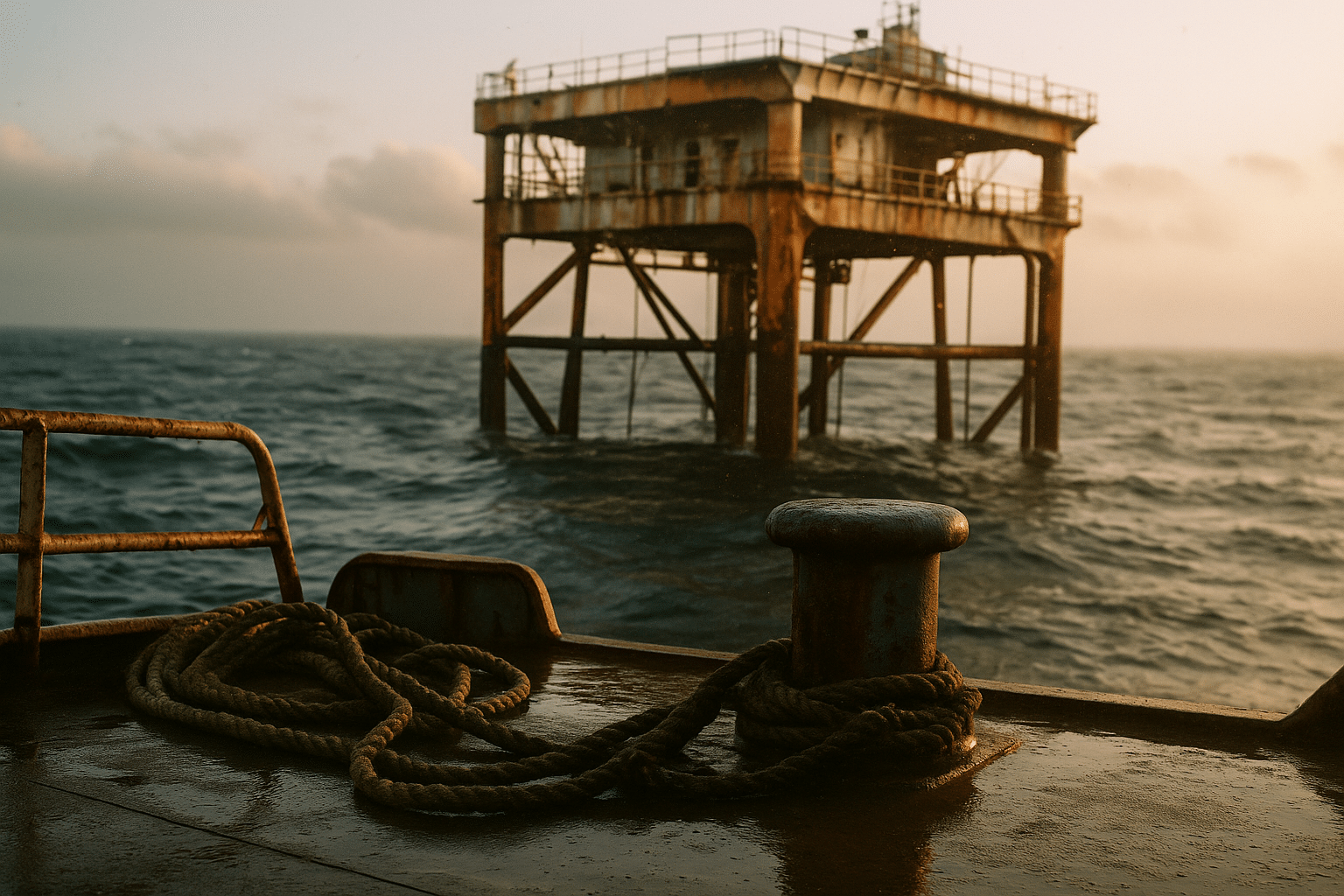

Marine and deck teams coordinate supply vessels, manage cranes and cargo, and handle mooring equipment. Helicopter administrators, radio operators, and permit coordinators keep personnel logistics and work authorization flowing. Catering and accommodation staff enable the entire workforce to function; well-rested, well-fed crews make fewer mistakes. Oversight by safety and environmental practitioners ensures permit-to-work processes, isolation procedures, and waste handling align with regulatory standards.

Typical daily rhythm:

– 05:30–06:30: Shift handover, toolbox talks, and job safety analyses

– Day shift: Planned maintenance, inspections, scaffold work, production tuning, and project tasks

– Night shift: Continuous operations, routine monitoring, cleaning, and prep for next day’s lifts

– Throughout: Control room trend checks, alarms response, and coordination with onshore support

Asset types shape the work. Fixed platforms sit in shallower waters with substantial topsides and robust access. Floating production systems—semi-submersibles, spars, and vessels adapted for processing—bring flexible moorings and subsea tie-backs that require different marine competence. Subsea fields shift substantial equipment to the seabed, moving more inspection work to remotely operated vehicles. Across designs, the core rules are similar: clear responsibilities, verified isolations, and disciplined communication. A dependable worker is one who can follow procedure, think a step ahead, and flag deviations early.

Safety Culture and Risk Management — Systems That Protect People and Assets

Safety offshore is not just a set of rules; it is a system of habits that turns high-risk tasks into controlled ones. The foundation is hazard identification and risk assessment applied before and during work. Job safety analyses break tasks into steps, spotlight hazards, and specify controls. Permit-to-work systems authorize activities—hot work, confined space entry, electrical isolation—after cross-checking prerequisites. Lockout/tagout prevents inadvertent energization, and gas testing confirms atmospheres are safe. When these layers function together, the residual risk drops to acceptable levels.

Strong safety cultures emphasize coaching over blame. Near misses are collected and discussed so that weak signals—an almost-dropped tool, a surprising pressure spike—become lessons. Themes surfaced in many offshore incident reviews include hand injuries, line-of-fire exposures during lifting, and energy isolation errors. Controls that consistently reduce these risks include:

– Pre-lift walkdowns to confirm load paths and exclusion zones

– Standardized lifting plans and certified slings and shackles

– Independent verification of isolations, not just sign-offs

– Clear hand signals and radios with agreed phrases for stops

Emergency preparedness is regularly rehearsed: fire drills, man-overboard responses, lifeboat musters, and simulated helicopter incidents. Teams train to contain, communicate, and coordinate under stress. Medical facilities vary by asset size but commonly include trained medics, defibrillators, and telemedicine links to onshore doctors. Fatigue management is woven into safety: reasonable work-rest ratios, caffeine awareness near sleep times, and quiet hours in accommodation areas.

Regulatory frameworks differ by region but share a common intent: design for safety, assess major accident hazards, and maintain barriers. Independent verification bodies may review safety-critical elements such as blowout preventers, fire and gas detection, and emergency shutdown systems. Over the past decades, many basins have seen declining reportable incident rates, largely attributed to higher engineering standards, structured competency programs, and better data use. The remaining challenge is consistency—ensuring that the quieter days at sea do not relax the discipline that keeps barriers intact.

Life at Sea — Rotations, Wellbeing, and Logistics

Work schedules offshore are usually rotational: commonly 14 days on/14 days off, 21/21, or 28/28 depending on region and role. Shifts run about 12 hours, and crew changes bring fresh energy and new perspectives. Travel typically involves helicopter hop-outs from coastal bases, with sea transfers by supply vessel when required. The first hours on board include safety induction, cabin allocation, and a walk-through of muster points and survival gear. Orientation is as practical as it gets—know your exits, keep hard hats handy, and stow gear securely.

Accommodation resembles a compact dormitory. You’ll find shared cabins, laundry rotations, and a galley that becomes the social heart of the asset. Connectivity varies; some installations have stable internet for messaging, while others limit bandwidth to operational priorities. Recreation rooms might include treadmills, a few weights, a TV corner, and a shelf of well-traveled paperbacks. Small rituals are invaluable: a steady gym routine, a call home at predictable times, and a nightly checklist to wind down after bright lights and machinery noise.

Fatigue and focus are constant considerations. Practical habits help:

– Hydration and steady meal timing to avoid energy dips

– Earplugs and blackout curtains to improve daytime sleep on night shifts

– Short, regular stretch breaks to counter repetitive tasks

– Early flagging of issues—if a step feels off, pause and reassess with your lead

Weather shapes daily life. Swell forecasts influence crane lifts, helicopter flights, and work-at-height plans. Fog can postpone departures, turning a 14-day hitch into 15 or 16; flexible mindsets and patient families are assets in their own right. The upside is time off: many find that rotational schedules enable long stretches for study, side projects, or time with loved ones. Pay structures often include allowances for offshore work and overtime differentials, reflecting the unique demands of the environment. To thrive, commit to the basics: solid sleep hygiene, open communication with your supervisor, and respect for the chain of command that coordinates hundreds of moving parts, often under pressure.

Technology, Environment, and Project Types — How the Work Is Evolving

Offshore assets blend heavy equipment with advanced sensing and controls. Control rooms track process conditions and safety systems, while technicians use portable devices for work orders, procedures, and data capture. Predictive maintenance is increasingly common: vibration and temperature trends flag bearing wear before a pump fails. Subsea fields rely on remotely operated vehicles for inspection, cleaning, and valve operations at depths well beyond diver limits. On the surface, crane operators use cameras and proximity alarms to improve situational awareness in tight deck spaces.

Different project types bring distinct challenges. Fixed platforms provide stable walkways and extensive topsides layout, simplifying some maintenance tasks. Floating systems adapt to deeper waters and harsher environments, but motion affects lifting limits, work-at-height, and comfort. Tie-back developments connect smaller fields to host facilities via subsea pipelines and umbilicals, where leak detection, pigging schedules, and corrosion management become central topics. Decommissioning projects reverse the lifecycle: well plug and abandonment, topsides cleaning and cutting, and jacket removal—each with rigorous waste tracking and environmental steps.

Environmental performance is a growing priority. Typical focus areas include:

– Flaring reduction through improved process control and start-up planning

– Produced-water treatment optimization and responsible discharge monitoring

– Spill prevention via secondary containment and robust hose and flange management

– Noise and lighting adjustments to reduce impact on marine life where feasible

Power and emissions strategies are advancing. Some assets use power from shore or hybrid systems to reduce fuel consumption. Others adopt energy management dashboards that visualize consumption by major equipment, prompting operator interventions. Materials selection—coatings, cathodic protection, and corrosion-resistant alloys—extends asset life and lowers environmental risk. Cross-sector skills now matter: technicians familiar with offshore oil and gas often find their competencies relevant to offshore wind construction, cable laying, and marine operations. The common thread is disciplined work in a remote environment where preparation and craftsmanship are visible in every bolted flange and tested alarm.

Getting Hired and Moving Up — Training, Certifications, and Career Planning

Breaking into offshore work is achievable with a plan. Entry points include roustabout roles, deck crew, scaffolders, catering positions, and trainee technician posts. Trades backgrounds—mechanical fitting, electrical work, welding, instrumentation—map well to maintenance and operations. Marine pathways exist too, from deck rating to officer roles under maritime standards. What hiring managers look for is a blend of safety mindset, reliability, and a willingness to learn the procedures that govern life at sea.

Common prerequisites and credentials include:

– Offshore survival and helicopter escape training (often bundled in regional basic safety courses)

– Medical fitness certificates meeting offshore standards

– Evidence of safety awareness: hazard recognition, permit-to-work familiarity, and lockout/tagout basics

– Task-specific tickets: working at height, rigging and lifting, confined space, and scaffolding competencies

A concise resume helps. Emphasize practical achievements: the pump you rebuilt that restored production, the inspection plan you executed without rework, or the lifting plan you helped refine. Add volunteer leadership or sports that show teamwork and discipline. References from supervisors who will attest to punctuality and careful work can be decisive. During interviews, expect scenario questions: how you would stop a job, escalate concerns, or handle a sudden weather change impacting planned lifts.

Once hired, growth follows clear routes. Operations technicians can progress to control room positions, then to senior technician and supervisor roles. Maintenance paths lead from technician to planner/scheduler and reliability engineering support. HSE practitioners evolve from coordinator to advisor and auditor. Project exposure—brownfield modifications, turnarounds, or decommissioning—broadens perspective and employability. Keep a personal learning log: note procedures mastered, equipment models serviced, and lessons learned from drills and incidents. Consistent documentation reinforces competency assessments and supports applications for advanced roles.

Conclusion — Turning Interest into Action

Your next steps can be simple: identify a realistic entry role, complete core safety training, and build a fitness routine that suits rotational life. Network by attending local industry meetups, maritime events, or trade certification classes, and ask experienced workers about their routes and tips. Treat each hitch as a chapter in your portfolio—keep records, seek feedback, and volunteer for tasks that stretch you. Offshore work rewards preparation, humility, and steady effort; with those, you can chart a resilient career on the water.