How to Clean and Maintain Bee Nests Safely and Responsibly

Outline and Why Safe Bee‑Nest Cleaning Matters

Before we lift a single tool, let’s map the journey so the process stays organized and humane. Here is the quick outline you’ll follow:

– Overview: Why safe cleaning matters for bees and people

– Nest Types and Biology: Solitary vs. social species, materials, and life cycles

– Preparation and Safety: Legal, ethical, and personal protective steps

– Cleaning Methods: Step‑by‑step guidance for common nest setups

– Maintenance and Prevention: Keeping nests healthy and trouble‑free long‑term

Bee‑nest cleaning is not just a chore; it’s stewardship. Bees pollinate a significant portion of flowering plants and contribute to food production at a scale that quietly underpins daily life. Clean, well‑maintained nest sites reduce disease pressure, discourage parasites, and prevent property damage while honoring the essential role bees play. Thoughtful timing and gentle technique allow you to tidy spaces without disrupting brood cycles or harming foragers. When done right, cleaning is less “removal” and more “renewal,” setting the stage for a fresh season of pollination.

There are also practical reasons to get it right. Accumulated debris can harbor mold, mites, wax moths, and pathogens that spread within or between colonies. Old materials may trap moisture, leading to rot in boxes or the surrounding structure. On the human side, unmanaged nests in inappropriate locations can escalate the risk of stings, allergies, or structural damage. A methodical approach balances three aims: protect bee health, safeguard people and property, and comply with local rules that may regulate wildlife and managed insects.

Finally, a note on tone and intention: this guide favors nonlethal, low‑impact methods, and urges readers to avoid quick fixes that use harsh chemicals or cause needless disturbance. When a nest is active and relocation is required, trained professionals or experienced beekeepers are often the most reliable path. For inactive or seasonal nest sites—like bee hotels, bumblebee boxes, or vacated cavities—careful cleaning, modest disinfection, and smart design upgrades can make a measurable difference. The sections that follow unpack the how, when, and why with clear steps and real‑world examples, so your efforts are both safe and effective.

Understanding Bee Nests: Types, Materials, and Seasonal Biology

Cleaning strategies begin with the simple question: whose home is this? Many wild bees are solitary, often cited as the majority of species worldwide. Solitary females nest in cavities—hollow stems, drilled wood, beetle burrows, even shell fragments—or excavate tunnels in sandy soils. Their “nests” contain individual brood cells provisioned with pollen and nectar, separated by partitions made from materials like mud, leaves, petals, or resin. In contrast, social species such as honey‑making bees or bumblebees form colonies with wax comb, brood, food stores, and a living workforce. Each structure calls for different timing, tools, and caution.

Materials vary widely and influence cleaning choices. Wax comb can absorb scents and residues; wood can swell or crack; bamboo or paper tubes can harbor mites between fibers; mud partitions can hide parasitic larvae. Propolis—a resinous glue used by many bees—has antimicrobial properties but also sticks to everything. Understanding the substrate helps you pick methods that remove pathogens without leaving harmful residue. For example, mild heat or a light solution of oxygen‑based cleaner on empty equipment can sanitize porous surfaces, whereas metal or ceramic parts tolerate thorough scrubbing and long rinses.

Seasons dictate both safety and success. Solitary bees often have a predictable cycle: nest construction in spring or summer, development in sealed cells, and emergence the following season. Cleaning a bee hotel, then, is usually done after emergence windows, when the tubes are empty. Bumblebee colonies commonly decline naturally at season’s end, leaving the box inactive by late summer or fall—an appropriate window for cleanup. Social colonies in walls or structures are a different story: cleaning while a colony is active is unsuitable; professional removal and relocation may be required, followed by thorough sanitation of the now‑vacant cavity to deter reinfestation.

Environmental cues add nuance. Temperature and sunlight influence activity; cooler mornings or overcast days mean fewer foragers aloft, decreasing stress if you must work near bees. Local flora and bloom periods shift timelines; earlier or later emergence affects when a nest is truly vacant. Habitat context matters too: a nest shaded by dense vegetation retains moisture longer and may be prone to mold or fungus. By reading species, materials, and seasons together, you tailor a cleaning plan that aligns with biology rather than fighting against it.

Preparation and Safety: Legal, Ethical, and Personal Protective Measures

Preparation begins at the desk, not at the ladder. Check local regulations regarding wildlife protection, managed colonies, and removal of nests from buildings. Some species are shielded by law; some regions require permits or licensed professionals for live removal. Ethical preparation is just as important: plan to work only when a nest is confirmed inactive, or to coordinate with experienced beekeepers when relocation is appropriate. Never use pesticides or harsh chemicals on active nests; beyond risk to bees, residues can persist and harm other pollinators.

Personal safety is straightforward with the right gear. Wear a veil or head net, gloves, long sleeves, and closed shoes. Avoid scented soaps, hair products, or perfumes on the day of work, as strong fragrances can attract or irritate insects. Keep calm movements—no flailing or fast gestures that signal alarm. It helps to have a partner serve as a spotter and to establish a simple plan for retreat if activity spikes. Nearby children and pets should be kept at a distance.

Timing, weather, and workspace setup make a big difference. Aim for cooler parts of the day when foragers are less active, and avoid windy conditions that stress bees and complicate ladder use. Stage tools before you begin: scrapers, soft brushes, a container for debris, replacement tubes or blocks, a sealable bag for contaminated materials, and clean cloths. If disinfection is needed on empty equipment, prepare a mild solution and label it. A common approach is one part household bleach to nine parts water for sanitizing vacated woodenware; scaled to a small job, that could be roughly 0.21 liters of bleach mixed with about 1.9 liters of water. Rinse thoroughly and allow items to dry completely in the sun before reassembly, as UV light and airflow assist in reducing microbes.

Think about neighbors, too. A courteous heads‑up avoids surprises, especially if you will be working near shared fences or entrances. If you suspect the nest is of a species known for defensive behavior, consult local experts first rather than testing your luck. Finally, plan disposal. Debris that might contain parasites should be sealed and removed from the site. Compost clean plant material separately from suspect nest remnants, and keep contaminated items out of general green waste. These small steps keep people safe and prevent problems from spreading.

Step‑by‑Step Cleaning Methods for Different Nest Types

Each nest type responds to a slightly different rhythm, but the guiding principle is the same: proceed only when inactive, work gently, and leave no harmful residue behind.

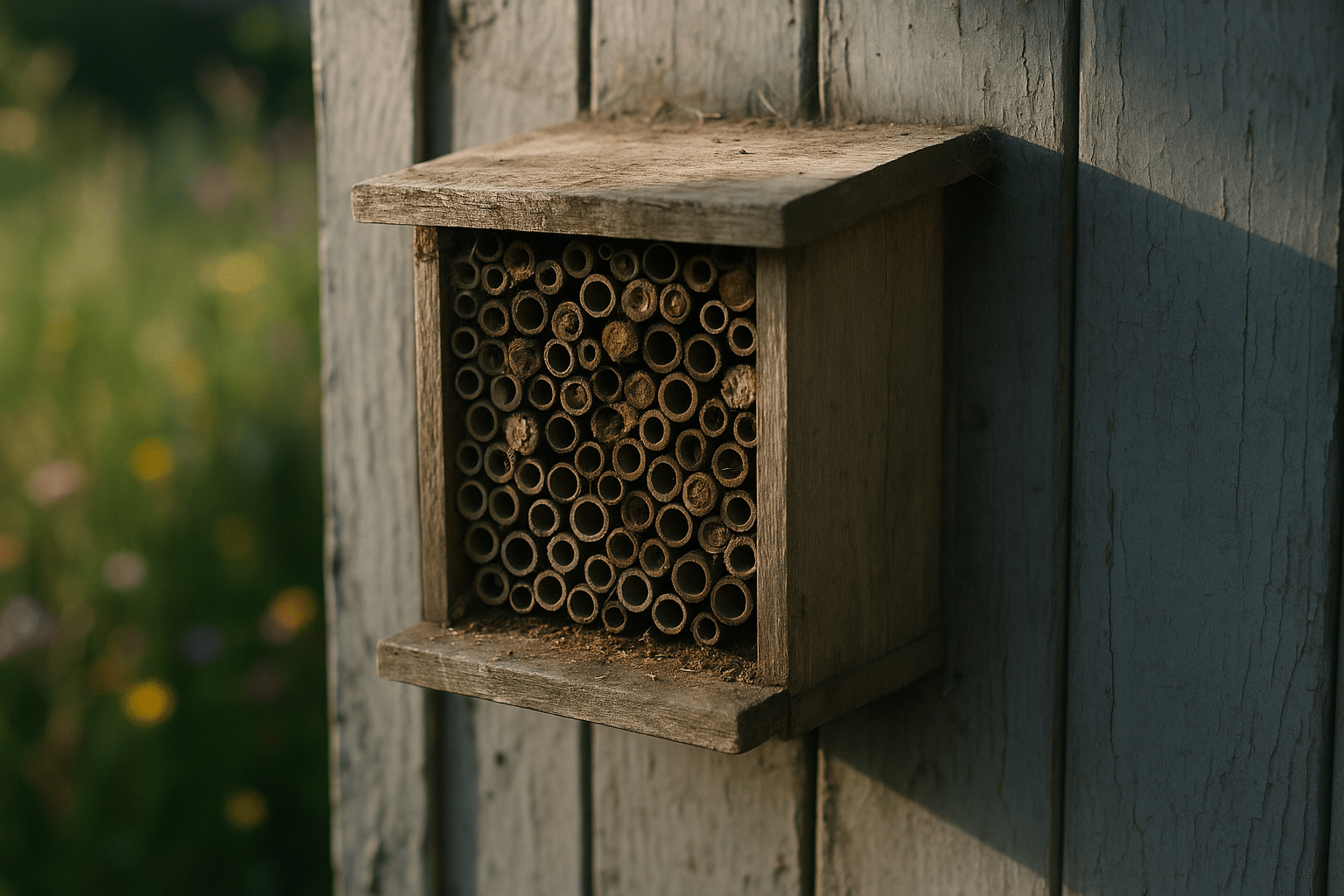

Solitary bee hotels (tubes and blocks): After the emergence period has passed, inspect the structure. Remove spent tubes or pull‑out liners and discard those with visible mold, frass, or parasite exit holes. If you collect cocoons during winter management, keep them dry, cool, and ventilated in labeled containers until safe release in spring, following species‑appropriate timing. For reusable wooden blocks, scrape debris from channels and consider using gentle heat on fully vacated components to discourage pathogens. Alternatively, soak removable parts in a mild sanitizing solution suitable for porous materials, rinse very thoroughly, and dry in sunlight. Replace any cracked or splintered pieces and standardize tube diameters so future residents fit well. To reduce future issues, install overhangs, orient toward morning sun, and keep the structure off the ground to improve drainage and airflow.

Bumblebee boxes: Wait until the colony naturally vacates at season’s end—look for a full week or two of inactivity. Wearing gloves and a mask, lift out old nest material (a mix of wax, fur, and plant fibers). Place suspect debris in a sealed bag for disposal. Wipe interior surfaces with a mild, non‑residual cleaner; oxygen‑based cleaners or a diluted vinegar solution on an empty box can help with odors and light staining. Rinse or wipe again with clean water and allow the box to dry completely. Replace damaged insulation pads with clean, dry natural fibers. Reassemble with a weatherproof lid, an upward‑tilted entrance to shed rain, and a small landing area that’s easy to inspect.

Vacated cavities in buildings: Once a social colony has been legally and safely removed by qualified hands, you may be left with wax, propolis, and residual scent. Carefully scrape wax and debris from the cavity, bagging all materials to keep pests from returning. Clean the area with a light sanitizing wash appropriate for the substrate, then rinse and dry. Seal entrances with proper materials and repair gaps so the space no longer broadcasts an open invitation. Consider adding physical deterrents like fine mesh over vents, keeping in mind ventilation requirements.

Across all types, a few universal don’ts apply: no pesticides inside nest structures, no solvent fumes, and no cleaning while larvae or pupae are present. Keep records of what you removed, how you sanitized, and when you finished. That simple log is your compass for the next season and a useful way to spot patterns—like which placements stay drier or which materials resist mold.

Maintenance, Monitoring, and Long‑Term Prevention

Cleaning day ends, but care continues. Maintenance is the art of preventing problems before they take root. Start with placement: a sheltered location with morning sun helps warm early foragers, while an overhang and slight forward tilt shed rain. Good ventilation reduces moisture, a primary driver of mold. Mounting nests on a stable structure minimizes vibration and deters predators. Keep vegetation trimmed back just enough to allow air movement without stripping away the natural cover bees appreciate.

Design upgrades matter. For bee hotels, opt for smooth‑walled tubes of appropriate diameters for local species; rough interiors trap mites and pollen residue. Use removable liners so you can replace them each season. Choose durable, untreated materials where possible to avoid off‑gassing. In bumblebee boxes, add a narrow entrance tunnel to reduce intrusion by rodents and wasps. Simple features—drainage holes, a sloped roof, and breathable insulation—can mean the difference between a thriving nest and a damp disappointment.

Monitoring is part gentle science, part mindful routine. Set a monthly check during active seasons to look for signs of moisture, parasites, or structural damage. Keep a lightweight log that tracks occupancy, weather notes, and any interventions, such as swapping out damp tubes. If you encounter pests, respond proportionally: remove and dispose of infested components, clean surrounding areas, and improve ventilation. Reserve strong measures only for empty equipment to avoid collateral harm. When in doubt about identification or severity, consult local naturalists or experienced keepers for advice tailored to your region.

Prevention extends beyond the box. Plant a succession of nectar and pollen sources that bloom from early spring through fall. Provide a shallow water source with pebbles for safe landing. Avoid broad‑spectrum insecticides in and around nesting areas; consider mechanical controls and habitat design to manage pests. Educate neighbors so they understand that a tidy, well‑placed nest site is an asset, not a nuisance. Finally, celebrate the small wins: the first returning female inspecting a tube, the quiet hum at sunrise, the clean structure ready for a new season. With attentive maintenance and thoughtful design, cleaning becomes a once‑a‑year ritual rather than a scramble, and your pollinator habitat can remain healthy, resilient, and welcoming.